This is the story of how my brother taught me to be true to myself. Thank you to The Story Collider for giving me the chance to tell it. Video above, audio below.

For more about my brother, read my original stories:

This is the story of how my brother taught me to be true to myself. Thank you to The Story Collider for giving me the chance to tell it. Video above, audio below.

For more about my brother, read my original stories:

It's been one year since I wrote "The Parallel Universe Where My Brother Lives", the story of how I tried to move on after my brother's suicide. Re-reading the story now, I remember how painful it was for me to even think about my brother. But “Parallel Universe” doesn’t fit with who I am now. Writing, sharing, and talking about my story was tremendously healing. For this anniversary, I want to explore what it is about stories that can be so healing.

Next to Normal honored what my family went through trying to support my brother.

Most of us feel like something is wrong when we're experiencing strong emotions. This happens to me a lot when I get mad. I remember running late to work one day and getting pushed into a dirty New York City puddle of water. I was soaking wet and smelled like sewer. All morning long I felt like I was losing my mind – I was furious, couldn't stop replaying the situation in my mind, and was flooded with criticizing thoughts ("You're so stupid for letting this happen to you").

It wasn't until I talked to a friend that I started to feel better. "I would have been so pissed off if that happened to me!" Hearing that helped me calm down. My friend helped me understand that my feelings made sense given the situation. The more she validated my feelings, the more comfortable I felt.

Validation is one of the main reasons why stories can be healing. By introducing characters who are experiencing similar situations, stories can make us feel less alone and make it easier to talk about what we're thinking and feeling. That's why coming of age films like The Breakfast Club, 10 Things I Hate About You, and The Perks of Being a Wallflower are so important – they validate the experience of being a teenager at a time when so much of the world can seem invalidating. It's also a big part of the psychology of cult TV shows like Firefly, Buffy, and Doctor Who.

Watching Broadway's Next to Normal was deeply validating for me. The musical is about a mother's struggle with bipolar depression and the impact it has on her family. Not only is the music beautiful (check out "I Miss the Mountains") but seeing the family’s struggle to support their loved one captured much of what happened to my family after my brother’s diagnosis.

Done right, stories can also reduce stigma about mental health. Many still believe problems with mental health are caused by personal weaknesses, that individuals should feel ashamed for their struggles, and treatment should be kept secret. We know this stigma has no basis in reality. Problems like anxiety and depression are caused by many biological, psychological, and environmental factors and affect a wide variety of people from all backgrounds. Stories can challenge these stigmatic beliefs and speak to the reality of mental health.

Often, the most helpful stories are true accounts of mental illness. That's why I'm a big fan of Glenn Close's Bring Change 2 Mind campaign, which encourages people to share their personal stories and start a dialogue about mental health.

Films such as A Beautiful Mind and books like The Boy Who Couldn't Stop Washing have also done a lot to tell the story of schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder. I also love what Temple Grandin has to say about autism and why the world needs all kinds of minds.

Reading Willy Linthout’s graphic memoir Years of the Elephant, a story about a father's struggle to mourn his son's suicide, went a long way to challenge my stigma about suicide. I used to think “I should be able to cope with this” but Linthout’s story taught me that most people grieving from a suicide go through a complicated process that lasts for a very long time. The Live Through This project also made this think our culture might be ready for a conversation about suicide.

Ellen Forney’s Marbles brings phenomenal clarity to the experience of therapy and medication.

Because of stigma, there’s a lot of confusion about what actually happens in therapy. Stories about mental healthcare have the power to demystify treatment. The best example of this is Ellen Forney’s graphic memoir Marbles. Forney shows what it’s like to be diagnosed with bipolar depression, what treatment with a psychiatrist looks like, the role of medication, and how things outside of traditional mental healthcare can help recovery. Marbles is a masterpiece in the world of graphic memoirs and should be required reading for all therapists in training.

I also use stories to explain what I am doing in treatment. As a cognitive behavioral therapist, I'm essentially a coach whose job it is to teach my patients new ways of coping with distressing feelings, intrusive thoughts, and challenging situations. Whenever I teach a patient a new skill, I link it to a story they're passionate about. Relaxation training becomes Jedi training, cognitive coping skills are linked to Harry Potter's patronus charm, and exposure therapy is grounded in Batman's origin story. That's what geek therapy means to me – using stories people love to make therapy more fun, relevant, and effective (for more on this topic listen to Geek Therapy's "How Comic Books Saved My Life" or read Dean Trippe's "Something Terrible" ).

Batman always reminded me that growth is possible after traumatic experiences.

So far, everything has focused on consuming stories. It turns out that creating your own story can also be very therapeutic.

Many scientists and clinicians believe that avoiding difficult thoughts and feelings is the common problem among all mental health concerns. Avoidance works in the short term but as a long term strategy it just ends up intensifying problems. Therapists Giorgio Nardone and Paul Watzlawick summarize this nicely:

“Clinical experience has shown that, ironically, it is often the patient’s very attempt to solve the problem that, in fact, maintains it. The attempted solution becomes the true problem.”

The solution is to help people experience all emotions, both the positive and the negative. That's the basis behind a number of effective treatments like exposure therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and the unified treatment for emotional disorders. Short-term focused writing about emotions can bring about many of the same effects. Psychologist James Pennebaker's research has shown that writing can reduce anxiety and depression while increasing immune functioning. Some therapies also integrate writing as a major part of treatment. Cognitive processing therapy, which is used to treat post-traumatic stress disorder, helps people get unstuck from their thoughts and develop meaning out of the events that have happened.

Just knowing that people can recover from traumatic experiences can make it possible for someone to start moving towards post-traumatic growth. Hearing stories about recovery from a loved one's suicide was key to my growth. My friend and colleague Melinda Moore shared her story with me, how recovery from her husband's suicide led her to become a psychologist who promotes suicide prevention. Hearing from her made me believe that I too could gain something from my loss.

Following difficult emotional experiences, the single best predictor of recovery is how much support someone gets from their friends and family. That's what made my recovery so difficult – I didn't talk about my pain with anyone so I didn't get much social support. Of course people asked how I was doing but I ignored them because I wasn't ready to open up.

When I did finally share my story, I was overwhelmed by messages of support. It wasn't just people I knew, but also individuals I never met who went out of their way to let me know they wanted to help. To date, I've received over 3,000 messages in response to “Parallel Universe”. I save each one and re-read them on particularly tough nights.

Katie Goldman, the "Star Wars girl"

Sharing a story, regardless of the way in which you do it, has the potential to activate a support network. One of my favorite examples of this comes from 7-year-old Katie Goldman. Katie was repeatedly bullied for bringing a Star Wars water bottle to school. Her mom wrote about the experience on her blog and asked for help. The story quickly spread across the internet. Here's how Katie's mom describes what happened next:

Katie is overjoyed by the comments coming in!!! My sweet first grade daughter has been sitting with me at the computer, reading aloud all the wonderful, supportive notes from readers, and her face is shining...We are going to print the comments out and make a book for her to read whenever she feels the need. Today she wore a Star Wars shirt to school and said to me, "Tell the people about it!!!!" This is really restoring her self confidence. She did a jaunty little pirouette in her Star Wars shirt before school.

The stories we develop about ourselves shape our behavior, filter our memories, and inform our decisions about the future. My story is now forever linked with "Parallel Universe". Every month it's the most widely read article on Brain Knows Better and it’s what I’m most known for outside of my professional work.

Like other survivors of suicide, a part of my life is now dedicated to promoting suicide prevention and helping others who are experiencing complicated grief. That’s why I’m announcing a new project that will turn my story (Growing Up Trekkie, Parallel Universe, Most Honest Year of My Life) into a graphic memoir. I hope to share this new story with you in one year’s time at the third anniversary of “Parallel Universe”.

This was written in honor of Mental Health Month and the American Psychological Association's Mental Health Blog Day. To hear more about the healing power of stories, check out the Super Fantastic Nerd Hour mental health episode.

Last May, I wrote about how my brother's suicide shattered my life and my attempt to move on. Writing that story was profoundly healing and helped me feel less shame about his death.

Today, in honor of World Suicide Prevention Day, I'm continuing the conversation with a story about why people become suicidal and what can be done to help them. I won't draw from real life this time (my brother’s story is not mine to tell). Instead, I'm using one of the most realistic depictions of suicide from science fiction – SyFy Channel's Battlestar Galactica.

I should warn you – this article includes details about the final season of Battlestar Galactica. If you want to avoid spoilers, it's best to save this for later.

Read More

It starts at home. I’m doing the dishes and listening to a podcast. I'm about to rinse off when my brother walks through the front door. “About time,” I think. Salman’s been gone for a while and I was beginning to wonder when he was coming back. We put on some tea, sit down and watch an old episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, making fun of Worf during the commercials.

That’s when I wake up.

I have this dream every other week. I hate it – not the dream, but being ripped away from it. Waking up is like finding out my brother died all over again.

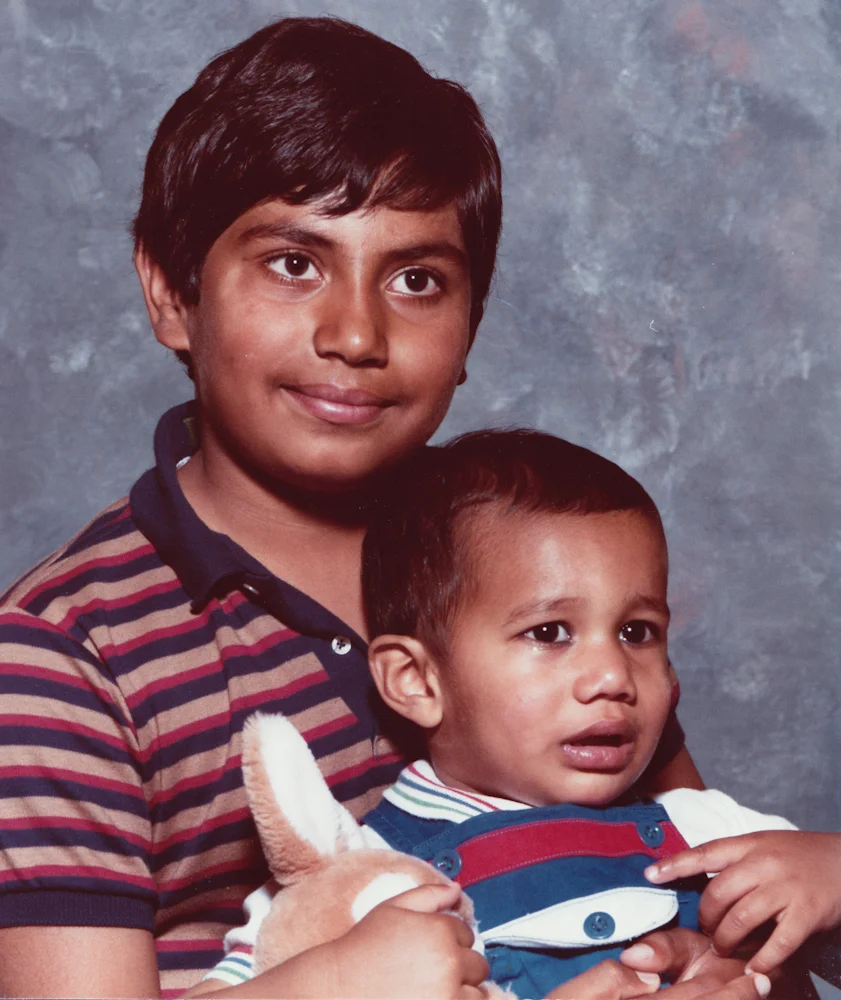

On May 19, 2008, Salman shot himself, ending a long battle with bipolar depression. He was 36 years old. Salman suffered in silence – his illness wasn’t diagnosed until he was 34, after a very public manic episode that tore my family apart.

The dreams are always the same – I’m living my life right now in New York City and then my brother appears. Life has continued as if he never died – he was just away for a while. I’ve come to think of these dreams as a parallel universe where he never committed suicide, an alternate timeline in which he lives.

Waking up reminds me of how I found out. I got a call from my dad at 4:46am that Monday morning. I can hear his trembling voice – “Ali, your brother is no longer on this Earth – he committed suicide.”

I remember my guilt – Why didn’t I do more to help him? What did I miss? Why wasn’t I there for him?

I get out of my bed, run through my morning routine, but the pain lingers. Listening to music and checking the news helps me bury my memories.

I could be having a normal day, then someone says, “My boss makes me want to shoot myself.” It feels like waking up again. How dare you joke about that? You have no fucking idea what you’re saying! But it’s just a figure of speech to them, what can you do but shove the anger down and get out of there as quickly as possible.

It’s worst when I physically can’t get away. Days after learning about Salman’s death I flew back to visit his grave in Pakistan and shared the seat with a man my father’s age. He looked easy to talk to.

“Are you on your way home?” he asked.

“Not really, I’m going to visit my parents.”

“Ah, good for you. I’m sure they’ll be happy to see you. I was here for my daughter’s graduation – she just finished med school.” He was beaming with pride.

We talked about the medical profession and my training to become a psychologist.

“How’d you get interested in that? Were your parents psychologists?”

“It’s what I loved most in college, honestly.”

“What do your siblings do?”

“No…no siblings,” I lied, “it’s just me.”

“Oh, an only child,” he nodded. Now he wanted to talk about it! “Growing up, you must have had all the pressure from your parents.”

I had to get out of that seat. I said “excuse me,” tore off my seat belt and went into the lavatory. Not to pee, just to stand there. My heart was racing. I couldn’t tell him the truth – that I had a brother and he just died. I didn’t know why, I just knew I couldn’t do it.

When I returned to my seat, I put on my headphones to block out the older man. Despite his efforts, we didn’t speak for the remainder of the flight.

I don’t remember much from that visit. I know a lot of people came to pay their respects, but the rest is a blur. What sticks out vividly is seeing his grave for the first time. I stayed with him for an hour. I promised Salman I would keep his memory alive with his son and pass on what he had taught me. In that moment, I was overcome by the smell of fresh jasmine, as if his spirit was trying to embrace me.

After returning home to Washington, D.C., I grouped people into two categories – those who knew me before my brother died and those I met after. Friends and family gave me a wide berth, avoiding the topic of Salman’s death. With new people, I pretended to be an only child. I hated myself for lying, but the last thing I wanted was to be the guy – the therapist – with the bipolar brother who shot himself. Denying Salman’s role in my life was the quickest way to avoid the pain. With the exception of my dreams, Salman never existed.

That year I spent Thanksgiving at my friend’s home and met her sister’s future fiancé, Karl. The two of us hit it off after we discussed a mutual appreciation of Batman and Iron Man. After dessert, a few of us played board games. Karl and I joined forces and declared ourselves “Team Awesome.”

“It was weird growing up,” said Karl, “My brother was 10 years older than me – he was a friend and a bit of a dad.”

I wanted to say “me too”, but I didn’t, I deflected and asked, “What was that like, being so far apart in age?”

“We did a lot of things together – sports and all that stuff, but he let me hang out with him and his friends, sometimes even sneaking me into rated-R movies.”

“Sounds like fun,” I said, but nothing more. In fact, Salman did the same. He took me to a bunch of movies I wasn’t old enough to see – Terminator 2, The Rock, The Matrix. My favorite thing was to tag along with him to Galactican, our local arcade. He knew everyone there. It made me feel so cool just being around him.

I didn’t tell Karl any of this. I might have made a good friend that day, but I kept pretty quiet.

“You know,” Karl said, “My brother helped me decide to major in computer science.”

“That’s cool,” was all I said, but inside I was screaming, I desperately wanted to tell Karl how my brother introduced me to Star Trek, how that led me to psychology, but I was too scared. I didn’t want him, or anyone else at the table, to ask questions, to judge me, to think poorly of my family.

By numbing myself to Salman’s suicide I restricted all of my memories about him – the bad and good. Remembering the experiences we shared together made me miss him dearly.

I think about that now – if Salman were alive today, he’d clear his schedule and take me to see the new Star Trek movie. I like to believe we’re both doing just that, in the parallel universe. Maybe in that universe he’s the best man at my wedding, the uncle to my kids, and my friend in old age.

Salman ended his life in order to stop his suffering. By refusing to face my pain, I’ve prolonged my suffering.

Last year I was serving on the board of directors of the American Psychological Association. At our end of year dinner, I sat next to Melba Vasquez, a past-president of the association. After some small talk, Melba started a conversation about family.

“Ten siblings!” she asked one of our colleagues. “What was that like, growing up in such a big home?”

“Jennifer, what about you – how big is your family?” Melba continued around the table, one by one.

I felt sick. I was stuck – nowhere to hide.

“Ali, what about you?”

“There were four of us, my parents and my older brother…but he died a few years ago. He had bipolar depression and took his own life.”

“I’m so very sorry, Ali,” she said. “I had no idea.”

“It’s not something I talk about.” Even as the words came out of my mouth, the whole situation felt unreal – I had never publically talked about Salman’s death before.

“That makes sense,” she said. “There’s so much stigma about suicide – it’s not something anyone talks about.” Melba always communicated with compassion and honesty – it was one of the reasons I looked up to her and why I couldn’t lie to her.

“I’ve always been afraid that people would think differently of me and my family. I had this fear that people would think I’m an incompetent psychologist because I couldn’t save my own brother.”

“I’ve felt that way at different times in my life. Clinicians are just as vulnerable to these things as anyone else.”

When I accepted that fact, I felt comfortable seeking out my own therapy.

Later that night, I told Melba the things I wanted to tell Karl – how my brother taught me to build computers, our late nights watching Twilight Zone, debating Captain Kirk versus Captain Picard.

Yes, as I talked about it I felt that pain, the pain of waking up, but I endured it.

This way of dealing with things has also kept me away from the people I love. I rarely speak to my parents and I’ve been terrified of calling my brother’s son. I’m ashamed to admit I haven’t kept my promise at Salman’s gravesite. The last time I spoke to my nephew he asked me, “Why don’t you call me Uncle Ali?” I didn’t have an answer for him.

I want to be able to remember Salman more. It’s taken me 5 years, but I’ve finally put up photos of my brother in my home. They sit next to the other reminders of him that have always been there – the starships, action figures, video games. The photos don’t just bring me pain, they remind me of the joy we shared together.

This was written in honor of Mental Health Month and the American Psychological Association's Mental Health Blog Day. I want to thank Razia Kosi, Executive Director of Counselors Helping (South) Asians/Indians (CHAI) for encouraging me to share my story. If you are a survivor of suicide, help is available at the American Association of Suicidology. If you are in crisis, please call 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

May 17, 2013 Update: Please read my thank you letter to all who reached out to me after reading this story.

September 10, 2013 Update: As a followup to this story, I wrote an article about how to help someone who is suicidal. Note - it includes spoilers about the end of Battlestar Galactica.

October 15, 2013 Update: This story won the 2013 Brass Crescent Award for Best Blog Post.

January 8, 2014 Update: For the final update to this story, please read "The Most Honest Year of My Life".

This website is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute clinical advice. All views, posts and opinions are my own unless they are quotes, links, or guest posts. Copyright © Ali Mattu. All rights reserved.