The internet was the forum for global fan outrage this week when Warner Brothers announced Ben Affleck will star as the Dark Knight opposite Henry Cavill's Man of Steel in 2015's Batman Versus Superman movie.

Fans have been complaining about two things.

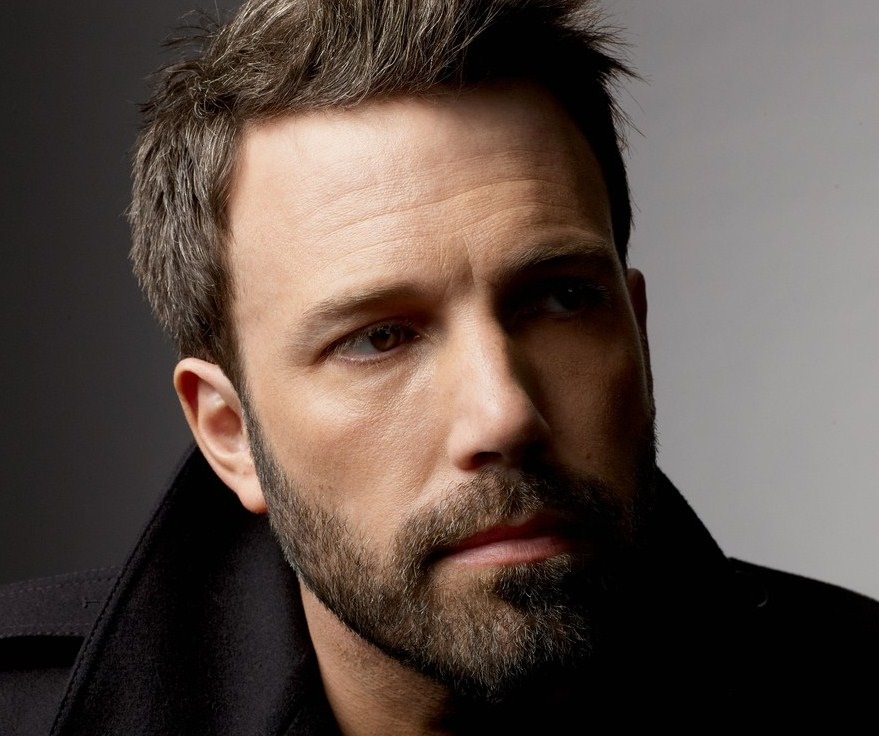

1. "Ben Affleck has been in really crappy movies, including his last superhero movie – Daredevil." Check out exhibit A:

Really looking forward to seeing Affleck bring the depth and gravitas to Batman that he brought to Daredevil and Gigli.

— Wil Wheaton (@wilw) August 23, 2013

2. "Ben Affleck can't pull off Bruce Wayne/Batman." Exhibit B:

Affleck gonna be like "It's the Jokah! Or the Riddlah! Rahbin! Call Commissionah Gahden!"

— D'Brickashaw (@DragonflyJonez) August 23, 2013

Rough stuff (and there's plenty more of it out there). At least one person stood up for Affleck:

Affleck'll crush it. He's got the chops, he's got the chin -- just needs the material. Affleck & Cavill toe to toe -- I'm in.

— Joss Whedon (@josswhedon) August 24, 2013

I was also surprised by this announcement and texted my Batman friends to vent. They eventually calmed me down and when I really thought about it, this whole debate didn't make much sense. We have nothing to judge Affleck's portrayal as Batman (they haven't even started filming yet). We also can't go by his past performances because they've been inconsistent (Gigli was stupid but Argo rocked).

But what we can dive into is the psychology of the Batfleck backlash, which was pretty much summed up in this tweet:

I love how the internet works. 1. Outrage. 2. Outrage over others' outrage. 3. Everyone forgets and buys the comic/watches the movie anyway.

— Chris (@CapSteveRogers) August 23, 2013

Patterns of fan outrage like this happen all the time – people get invested in something, feel betrayed by changes, and eventually come to terms with it. It's all because of the anonymity of the internet and a psychological safety mechanism called cognitive dissonance.

All This Has Happened Before and Will Happen Again

We've seen this type of outrage before – critics didn't like Michael Keaton's casting as Batman. "A comedian can't play the cape crusader!". Yet he did a pretty good job and (along with Christopher Reeve's Superman) paved the way for our modern age of superhero movies.

Fans were also pissed when they heard Heath Ledger, star of the teen flick 10 Things I Hate About You, was cast as the Joker. They loved Jack Nicholson's portrayal of the same character and doubted Ledger had the talent to bring to life Batman's archenemy. He went on to win a posthumous Oscar for that role.

Fan outrage isn't unique to Batman. Many longtime Trekkies hated Star Trek Into Darkness, despite its critical acclaim and blockbuster success. People were hostile when the new Battlestar Galactica reimagined the cigar smoking Starbuck into a female character. We see this when video game sequels make big departures from their predecessors (which has led to a wave of discrimination against game developers). Similar stuff happens in sports. Patriots fans mocked Tim Tebow when he was signed on to the team. Even Facebook users ballyhoo each and every interface change the social networking website makes.

(Anger + Anonymity) - Eye Contact = Internet Trolls

Regardless of the product, fans spend a lot of time, energy, and money investing in the way things are. For a lot of people, anger is a natural reaction when we think something we love is changing for the worse.

While there are a lot of reasons why people get mad, it all comes down to feeling wronged – something has happened that was not okay (like having your foot stepped on in the subway, someone cutting in front of you in a line, or having your wallet stolen). Anger warps our thoughts, jumpstarts our body, and makes us want to break something. Whether or not we act on our aggressive urges depends on the circumstances of our anger.

Me and my favorite Bruce Wayne - Kevin Conroy from Batman: The Animated Series & Arkham City.

Batman fans have invested a lot in the superhero. Take me for example. I fell in love with the character after seeing Batman: The Animated Series. Batman gave me hope that I too could grow from difficult experiences and develop the skills I needed to overcome my own super-villains. I own all of the movies on Blu-ray, have met my favorite Batman (Kevin Conroy), and nearly wet my pants when I saw the epic San Diego Comic-Con reveal of the Batman VS. Superman movie. I've been waiting my whole life to see Batman and Superman appear together on the big screen. The Affleck casting made me question if Warner Brothers was taking the movie as seriously as I was (yes, fans feel like they have a personal ownership over this kind of stuff).

When you take that type of anger and combine it with the internet, very bad things can happen. The internet loosens our inhibitions (kinda like alcohol) because we feel anonymous. A recent experimental study supported this idea and found that lack of eye contact with other people is one of the most important predictors of crazy online troll behavior. In other words, the things that keep us civil towards each other (like looking at someone face-to-face) are often stripped away on the internet.

Anger doesn't last forever — it comes and goes (just like all emotions). But we feel impulsive when we're angry and the internet gives us a way to quickly act on our impulses. Without face-to-face contact, we feel like we can say heinous things and get away with it.

We Want to be Consistent

Psychological science has demonstrated time and again that humans aren't rational beings. We feel first, think and act later. That's why we do things that don't make logical sense like smoking when we know it's bad for our health, procrastinating on our work even though it'll make things harder later on, and avoiding difficult conversations which end up prolonging our stress.

Sometimes our emotions lead us to do things that conflict with our beliefs. We might think we're generous people but then we avoid beggars on the street. That's where cognitive dissonance comes in. Our mind strives for consistency between our beliefs and actions. When there's an inconsistency ("I'm a good person but I didn't give money to that poor person"), our mind either changes our behavior ("I'll volunteer at a soup chicken") or modifies our beliefs ("If I gave that beggar money, they'd just spend it on beer or drugs"). These types of mental gymnastics happens all the time without any conscious awareness.

What does this have to do with Batfleck outrage? Cognitive dissonance helps us understand what's been going on inside the minds of fans after their initial anger has worn off. Here's an example:

Belief 1: I love Batman.

Belief 2: I hate Ben Affleck.

Dissonance: Ben Affleck is the new Batman!

We want to be consistent and these two beliefs just don't mesh with each other. To reduce our conflict, we might change the first belief and say "Affleck will never be my Batman" or "This isn't a serious Batman movie with Zack Snyder at the helm." Others will change their second belief – "Ben Affleck isn't that bad" or "Far worse actors have played Batman". Again, this is a stealthy process that happens without us even realizing it.

I wish the conversation about our new Batman was more civil, but with the way most of the internet works (no face time), that’s not going to happen. Knowing what we do about cognitive dissonance, Cap. Steve Rogers is right — people will get used to this news and see the movie anyway.

At the end of the day, it's good that people are reacting so strongly. Emotional reactions mean people care about Batman and are invested in the franchise. The moment fans stop caring is when a franchise dies (Exhibit C: George Clooney's Batman & Robin). Will Batman VS. Superman go down the path of Batman & Robin or Batman Begins? It’s just too early to tell.

November 21st 2013 Update: Listen to Geek Therapist Josué Cardona and I discuss Ben Affleck and Nerd Rage on the Geek Therapy Podcast.

December 22nd 2014 Update: Watch the Nerd Nite version of this article.