Presented without comment.

Thank You

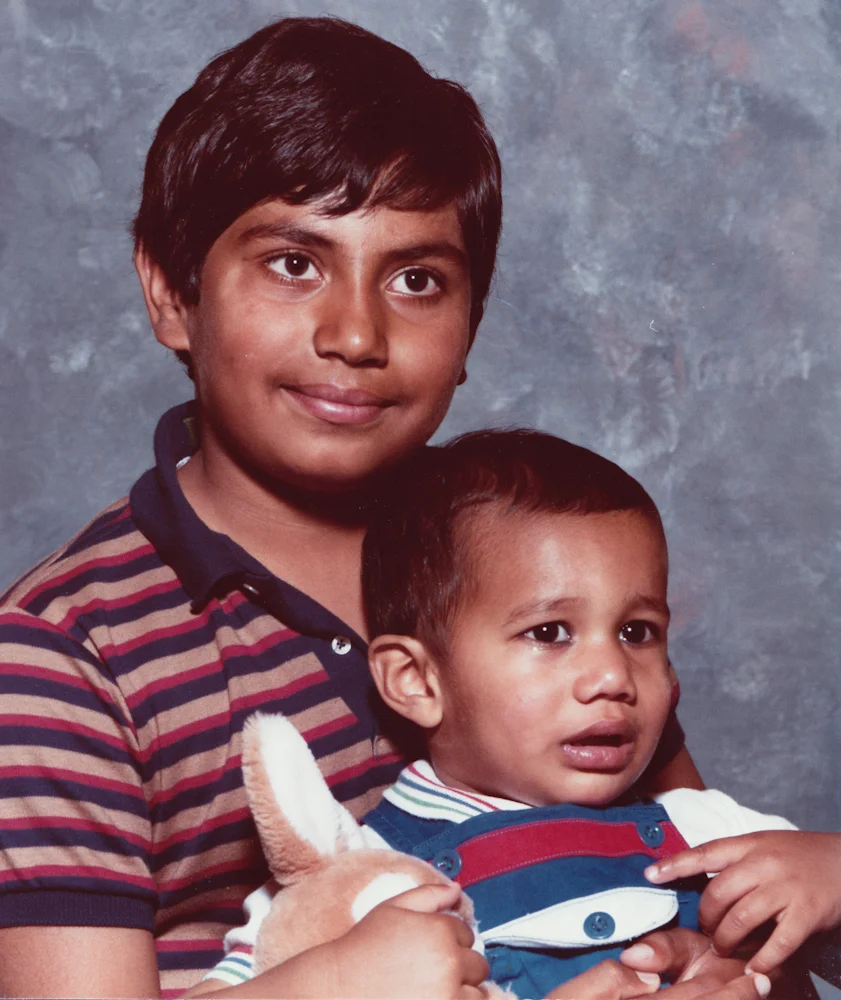

Wednesday's story about my brother's suicide lived in my head for 5 years. It was too private and painful to share with the world. When I was finally ready, writing seemed like the easiest way to start talking about it.

Your response has been overwhelming. Parallel Universe was quickly shared across social media, leading to thousands of visitors. Messages poured in from people who lost a loved one, were impacted by mental illness, or struggled with issues that aren't discussed in society. A few of you shared your memories of my brother.

Your words have been profoundly healing. The more I talk about Salman, the less shame I feel. It might take me awhile to get back to all of you, but I promise to keep the conversation going.

Thank you for helping me keep the memory of my brother

alive.

The Parallel Universe Where My Brother Lives

It starts at home. I’m doing the dishes and listening to a podcast. I'm about to rinse off when my brother walks through the front door. “About time,” I think. Salman’s been gone for a while and I was beginning to wonder when he was coming back. We put on some tea, sit down and watch an old episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, making fun of Worf during the commercials.

That’s when I wake up.

I have this dream every other week. I hate it – not the dream, but being ripped away from it. Waking up is like finding out my brother died all over again.

On May 19, 2008, Salman shot himself, ending a long battle with bipolar depression. He was 36 years old. Salman suffered in silence – his illness wasn’t diagnosed until he was 34, after a very public manic episode that tore my family apart.

The dreams are always the same – I’m living my life right now in New York City and then my brother appears. Life has continued as if he never died – he was just away for a while. I’ve come to think of these dreams as a parallel universe where he never committed suicide, an alternate timeline in which he lives.

Waking up reminds me of how I found out. I got a call from my dad at 4:46am that Monday morning. I can hear his trembling voice – “Ali, your brother is no longer on this Earth – he committed suicide.”

I remember my guilt – Why didn’t I do more to help him? What did I miss? Why wasn’t I there for him?

I get out of my bed, run through my morning routine, but the pain lingers. Listening to music and checking the news helps me bury my memories.

I could be having a normal day, then someone says, “My boss makes me want to shoot myself.” It feels like waking up again. How dare you joke about that? You have no fucking idea what you’re saying! But it’s just a figure of speech to them, what can you do but shove the anger down and get out of there as quickly as possible.

It’s worst when I physically can’t get away. Days after learning about Salman’s death I flew back to visit his grave in Pakistan and shared the seat with a man my father’s age. He looked easy to talk to.

“Are you on your way home?” he asked.

“Not really, I’m going to visit my parents.”

“Ah, good for you. I’m sure they’ll be happy to see you. I was here for my daughter’s graduation – she just finished med school.” He was beaming with pride.

We talked about the medical profession and my training to become a psychologist.

“How’d you get interested in that? Were your parents psychologists?”

“It’s what I loved most in college, honestly.”

“What do your siblings do?”

“No…no siblings,” I lied, “it’s just me.”

“Oh, an only child,” he nodded. Now he wanted to talk about it! “Growing up, you must have had all the pressure from your parents.”

I had to get out of that seat. I said “excuse me,” tore off my seat belt and went into the lavatory. Not to pee, just to stand there. My heart was racing. I couldn’t tell him the truth – that I had a brother and he just died. I didn’t know why, I just knew I couldn’t do it.

When I returned to my seat, I put on my headphones to block out the older man. Despite his efforts, we didn’t speak for the remainder of the flight.

I don’t remember much from that visit. I know a lot of people came to pay their respects, but the rest is a blur. What sticks out vividly is seeing his grave for the first time. I stayed with him for an hour. I promised Salman I would keep his memory alive with his son and pass on what he had taught me. In that moment, I was overcome by the smell of fresh jasmine, as if his spirit was trying to embrace me.

After returning home to Washington, D.C., I grouped people into two categories – those who knew me before my brother died and those I met after. Friends and family gave me a wide berth, avoiding the topic of Salman’s death. With new people, I pretended to be an only child. I hated myself for lying, but the last thing I wanted was to be the guy – the therapist – with the bipolar brother who shot himself. Denying Salman’s role in my life was the quickest way to avoid the pain. With the exception of my dreams, Salman never existed.

That year I spent Thanksgiving at my friend’s home and met her sister’s future fiancé, Karl. The two of us hit it off after we discussed a mutual appreciation of Batman and Iron Man. After dessert, a few of us played board games. Karl and I joined forces and declared ourselves “Team Awesome.”

“It was weird growing up,” said Karl, “My brother was 10 years older than me – he was a friend and a bit of a dad.”

I wanted to say “me too”, but I didn’t, I deflected and asked, “What was that like, being so far apart in age?”

“We did a lot of things together – sports and all that stuff, but he let me hang out with him and his friends, sometimes even sneaking me into rated-R movies.”

“Sounds like fun,” I said, but nothing more. In fact, Salman did the same. He took me to a bunch of movies I wasn’t old enough to see – Terminator 2, The Rock, The Matrix. My favorite thing was to tag along with him to Galactican, our local arcade. He knew everyone there. It made me feel so cool just being around him.

I didn’t tell Karl any of this. I might have made a good friend that day, but I kept pretty quiet.

“You know,” Karl said, “My brother helped me decide to major in computer science.”

“That’s cool,” was all I said, but inside I was screaming, I desperately wanted to tell Karl how my brother introduced me to Star Trek, how that led me to psychology, but I was too scared. I didn’t want him, or anyone else at the table, to ask questions, to judge me, to think poorly of my family.

By numbing myself to Salman’s suicide I restricted all of my memories about him – the bad and good. Remembering the experiences we shared together made me miss him dearly.

I think about that now – if Salman were alive today, he’d clear his schedule and take me to see the new Star Trek movie. I like to believe we’re both doing just that, in the parallel universe. Maybe in that universe he’s the best man at my wedding, the uncle to my kids, and my friend in old age.

Salman ended his life in order to stop his suffering. By refusing to face my pain, I’ve prolonged my suffering.

Last year I was serving on the board of directors of the American Psychological Association. At our end of year dinner, I sat next to Melba Vasquez, a past-president of the association. After some small talk, Melba started a conversation about family.

“Ten siblings!” she asked one of our colleagues. “What was that like, growing up in such a big home?”

“Jennifer, what about you – how big is your family?” Melba continued around the table, one by one.

I felt sick. I was stuck – nowhere to hide.

“Ali, what about you?”

“There were four of us, my parents and my older brother…but he died a few years ago. He had bipolar depression and took his own life.”

“I’m so very sorry, Ali,” she said. “I had no idea.”

“It’s not something I talk about.” Even as the words came out of my mouth, the whole situation felt unreal – I had never publically talked about Salman’s death before.

“That makes sense,” she said. “There’s so much stigma about suicide – it’s not something anyone talks about.” Melba always communicated with compassion and honesty – it was one of the reasons I looked up to her and why I couldn’t lie to her.

“I’ve always been afraid that people would think differently of me and my family. I had this fear that people would think I’m an incompetent psychologist because I couldn’t save my own brother.”

“I’ve felt that way at different times in my life. Clinicians are just as vulnerable to these things as anyone else.”

When I accepted that fact, I felt comfortable seeking out my own therapy.

Later that night, I told Melba the things I wanted to tell Karl – how my brother taught me to build computers, our late nights watching Twilight Zone, debating Captain Kirk versus Captain Picard.

Yes, as I talked about it I felt that pain, the pain of waking up, but I endured it.

This way of dealing with things has also kept me away from the people I love. I rarely speak to my parents and I’ve been terrified of calling my brother’s son. I’m ashamed to admit I haven’t kept my promise at Salman’s gravesite. The last time I spoke to my nephew he asked me, “Why don’t you call me Uncle Ali?” I didn’t have an answer for him.

I want to be able to remember Salman more. It’s taken me 5 years, but I’ve finally put up photos of my brother in my home. They sit next to the other reminders of him that have always been there – the starships, action figures, video games. The photos don’t just bring me pain, they remind me of the joy we shared together.

This was written in honor of Mental Health Month and the American Psychological Association's Mental Health Blog Day. I want to thank Razia Kosi, Executive Director of Counselors Helping (South) Asians/Indians (CHAI) for encouraging me to share my story. If you are a survivor of suicide, help is available at the American Association of Suicidology. If you are in crisis, please call 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

May 17, 2013 Update: Please read my thank you letter to all who reached out to me after reading this story.

September 10, 2013 Update: As a followup to this story, I wrote an article about how to help someone who is suicidal. Note - it includes spoilers about the end of Battlestar Galactica.

October 15, 2013 Update: This story won the 2013 Brass Crescent Award for Best Blog Post.

January 8, 2014 Update: For the final update to this story, please read "The Most Honest Year of My Life".

Can 9/11 Help Us Understand Star Trek Into Darkness? 5 Non-spoiler Predictions From the Psychology of Terrorism.

Vulcan's destruction was a 9/11 event.

Some Trekkies believe J.J. Abrams's first Star Trek film didn't include social commentary, that it didn't tackle the issues of our time. But that's just not true. Vulcan's destruction was a 9/11 attack against the United Federation of Planets. It occurred by an unknown terrorist, brought an end to feelings of safety, and seismically changed what it meant to be a citizen of the Federation - just like 9/11 in America.

This isn't my idea. I got it from Damon Lindelof, one of the guys who produced Star Trek:

“We often referred to the destruction of Vulcan as the 9/11 moment of [Star Trek]. There had to be an event that was so significant that it allows you to change the Trek universe, not just for the purposes of the first movie, but moving forward. The idea of saying, if you did something that huge, what would be the effect of that rippling outwards?”

This week we get to see the sequel, Star Trek Into Darkness. It's clear from the trailers and interviews that the new film continues the 9/11 thread of the first. Here's how Chris Pine (Captain Kirk) described the movie:

“It’s about terrorism, about issues we as human beings in 2013 deal with every day, about the exploitation of fear to take advantage of a population, about physical violence and destruction but also psychological manipulation. John Harrison is a terrorist in the mold of those we’ve become accustomed to in this day and age.”

Since we have over a decade of research on how America changed after 9/11, I wondered if I could we use the psychology of terrorism to predict the events of Star Trek Into Darkness? This is my attempt to do just that.

A quick note before we get started. Even though Star Trek Into Darkness is already out in many parts of the world, I don't know what actually happens in the film. I did get a spoiler over the weekend (which led to a rant about how spoilers are evil), but that spoiler wasn't related to the larger plot of the movie. My predictions are purely based on my knowledge of psychological science as well as exposure to canonical content (e.g. Star Trek Into Darkness trailers, Countdown to Darkness graphic novel, and Star Trek: The Video Game). There are no spoilers in this article, just my educated guesses.

Prediction #1: Starfleet Is Emotionally Compromised

Their is clear scientific consensus that 9/11 increased rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Even people who weren't directly exposed to the devastation of the attacks were at risk for trauma, leading some scientists to question the way we diagnose PTSD. While rates came down to normal a few years after 9/11, the two groups that continued to be at an increased risk for PTSD were first responders and immediate victims of the attack. First responders had multiple exposures to trauma while survivors faced years of chronic stress as they rebuilt their lives.

These findings make two groups at risk for PTSD in Star Trek - Starfleet officers and Vulcans. Starfleet, the Federation's first responders, witnessed the destruction of their fleet and the genocide of the Vulcan people. Many of them were also probably involved with humanitarian efforts after the attack, furthering their exposure to trauma. We know about 10,000 Vulcans (out of 6 billion) escaped the destruction of their planet. Every surviving Vulcan has been impacted by this attack, lost loved ones, and saw their home destroyed (through a viewscreen or on the news). Many Vulcans were exposed to additional trauma when the Gorn attacked New Vulcan (see Star Trek: The Video Game).

The person most likely to develop PTSD symptoms in Star Trek Into Darkness is Spock. Spock witnessed his mother’s death, saw his planet destroyed, identifies as a member of "an endangered species", and has a history of struggling with emotions (he attacked kids who were teasing him for being half Human/half Vulcan and attacked Kirk on the bridge of the Enterprise). We've already seen him re-experiencing the trauma of Vulcan's destruction in Countdown to Darkness. The movie will give us a deeper look into how Spock is responding to these traumatic events.

Prediction: We'll see Spock re-experience the trauma of Vulcan's destruction, try to numb his pain, and lose complete emotional control (and probably beat the crap out of someone).

Prediction #2: Xenophobia Will Rise

Star Trek Into Darkness may focus on Klingon xenophobia.

Discrimination against Arab and Muslim Americas skyrocketed post 9/11. Between 1998 to 2000, there were less than 10 incidents of Anti-Arab/Muslim hate crimes. Compare that with the 700 reported in the first 9 months after 9/11. Since the terrorists involved in the hijackings couldn't be brought to justice, many Americans took out their anger on those they thought looked like the enemy (which was based purely on prejudice and stereotypes).

I don't think we'll see the Federation become prejudiced towards Romulans (they look just like Vulcans). Instead, the Federation is going to become highly cautions of unknown alien threats in the galaxy (probably the Klingons, since they're in Countdown to Darkness). This post-Vulcan Federation won't be as inclusive and welcoming as the old – it’s been changed. To paraphrase Jack Beatty, this Federation has been "expelled from Utopia".

Prediction: Starfleet will act with extreme prejudice against the Klingons (for no reason) and see them as a threat to the Federation.

Prediction #3: The Prime Directive Will Be Challenged

Starfleet Command will debate breaking its guiding rule #1.

Research into the political aftermath of 9/11 is messy. Studies have revealed different, sometimes conflicting, findings. Some saw an increase in American conservatism after 9/11. Others identified a polarization of existing politics - liberals became more liberal, conservatives more conservative.

One of the most interesting, experimental, findings was the relationship between artificially created anxiety and anger in political decision-making. People who felt anxiety about terrorism endorsed opposition to aggressive domestic and foreign policies (e.g. increased homeland security, war against Iraq, etc.) while anger strongly increased support for war aboard. This makes sense - anxiety makes us exaggerate dangers and avoid situations while anger reminds us that we've been wronged and pushes us towards conflict. Even though anger and anxiety waxed and waned in the 2000s, American politics led to an erosion of individual freedoms in the interest of national security.

Star Trek Into Darkness will explore a similar theme. The focus won't be on civil liberties. Rather, the Federation may break its general order number 1: the Prime Directive. Countdown to Darkness is all about a character ignoring the Prime Directive for the sake of saving innocent lives. We're going to see a similar debate in this movie. Maybe even Section 31, Starfleet's covert intelligence agency, will be involved.

Prediction: A new terrorist attack will enrage the Federation, leading it to break the Prime Directive in the interest of protecting its citizens.

Prediction #4: John Harrison Is Motivated By Humiliation

Its been difficult to study the factors that influence individuals to engage in terrorism. This isn't exactly a population that's interested in contributing to research.

Most of what we know is based upon retrospective studies and field research. Some surprising findings indicate that most terrorists don't have religious education. Instead, many are college-educated professionals. This helps terrorist groups like al-Qaeda retain skilled agents. Terrorist become radicals in their late teens/early 20s, have incomplete knowledge of their religion, and aren't motivated by religious factors or poverty.

Terrorists are motivated by their social network (i.e. peer pressure), the belief that a foreign power has interfered with their country, an ingroup/outgroup identity (it's us versus them), and a sense of national humiliation. The humiliation is a big deal - feeling as though their people experienced problems under a foreign occupation (like marginalization), experienced chronic frustrations, and lost significance are good predictors of radical terrorism.

The villain in Star Trek Into Darkness is Benedict Cumberbatch's John Harrison. Who Harrison is, what he does, and what motivates him has been the topic of intense debate on the internet. Some think he is Khan, Star Trek's most iconic villain. I don't think he is Khan, but I do think he's a genetically augmented human like Khan, potentially one of Khan's allies. Like most terrorists, Harrison will be motivated by strong humiliation. Harrison will discover a plan by the Federation to persecute his people (augmented humans) and he will strike back with a campaign of terrorism.

Prediction: John Harrison, a Section 31 agent, discovers a Federation plot to kill augmented men, women, and children. In retaliation, he attacks Starfleet Headquarters.

Prediction #5: Resilience & Altruism Flourish

Someone will sacrifice their life in Star Trek Into Darkness.

Americans met the challenge of 9/11 with resiliency and altruism. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, people felt closer to one another, made blood donations, volunteered, contributed to charity, and increased trust in their communities. Character strengths of gratitude, hope, kindness, leadership, love, spirituality, and teamwork also significantly increased. Why did this happen? After large disasters, our sense of responsibility to each other increases, thereby encouraging acts of altruism. What was unique about 9/11 was American's strong desire to learn more about Islam - the Quran became a bestselling book and many efforts were put into place to increase religious understanding between different communities.

Gene Roddenberry's vision of Star Trek is an optimistic future. Therefore, Into Darkness will demonstrate humanity at its best. The crew will face immense challenges, but they’ll remain resilient in the face of traumatic stress. The Federation might engage in questionable moral actions, but Kirk will correct the Federation's mistakes. Someone will demonstrate ultimate altruism by sacrificing their life to save Earth.

Prediction: Kirk will do the right thing, even if it means losing his command. A member of the crew (not Spock) will sacrifice their life to save Earth.

This wraps up my countdown to Star Trek Into Darkness. Come back Sunday for my initial non-spoiler review of the film and check back in a few weeks for my analysis of the psychology of Star Trek Into Darkness.

3 Reasons Why the Psychology of Spoilers Is Wrong

Star Trek Into Darkness was just spoiled for me. I wasn't looking for spoilers - I've been avoiding plot details like the plague. I accidentally came across them on the internet while I was looking for something else.

I had a good plan - avoid scifi websites, don’t read social media, and clear my schedule to see the movie the moment it’s released. While I have tickets for the first night of fan screenings on Wednesday, the movie already came out in most of the world. This really irritated me - J.J. Abrams wants to preserve the magic of mysteries, so why release the movie at different times throughout the world?!? This guarantees that any citizen of the internet will get exposed to some plot details before they even have the chance to see Star Trek Into Darkness.

Spoilers piss me off. I love walking into a movie without any knowledge of what's going to happen. It's not about the plot - it's about going on the journey the filmmakers intended. I want to be moved, to feel something. Spoilers destroy that experience for me and it's getting harder and harder to avoid them.

But the science of spoilers says I’m wrong, that I’ll enjoy the experience even more once it's been spoiled. While it's a total confirmation bias on my part, I'm here to tell you the science is wrong - at least our interpretation of it is.

The Psychology of Spoilers

Results indicate people like stories better if they've been spoiled (Leavitt & Christenfeld, 2011).

To date, there’s been only 1 experiment about spoilers (Story Spoilers Don’t Spoil Stories). Psychologists Jonathan D. Leavitt and Nicholas J. S. Christenfeld of the University of California, San Diego had 819 (176 male, 643 female) undergraduate students participate in an experiment in which they read 3 stories they had not read before. Each was written by a real author (John Updike, Roald Dahl, Anton Chekhov, Agatha Christie, and Raymond Carver) and included ironic-twists, mysteries, and evocative literary stories. Story were either unspoiled, spoiled before reading, or a spoiler was included in the introductory text. Participants were then asked to rate their enjoyment of the story.

Across all conditions, people enjoyed the spoiled stories the most. Here's what the researchers have to say about their results:

Writers use their artistry to make stories interesting, to engage readers, and to surprise them, but we found that giving away these surprises makes readers like stories better...spoilers may allow readers to organize developments, anticipate the implications of events, and resolve ambiguities that occur in the course of reading. It is possible that spoilers enhance enjoyment by actually increasing tension. Knowing the ending of Oedipus Rex may heighten the pleasurable tension caused by the disparity in knowledge between the omniscient reader and the character marching to his doom. This notion is consistent with the assertion that stories can be reread with no diminution of suspense…Erroneous intuitions about the nature of spoilers may persist because individual readers are unable to compare spoiled and unspoiled experiences of a novel story.

In non-academic speak, spoilers may help people understand stories. Knowing what's going to happen might also make things more fun by giving you something to look forward to. This is supported by the research on rereading stories – most people enjoy a story as much, if not more, the second time they read it.

I gotta admit, the experiment itself is pretty rock solid. It had a large sample size, was well counter-balanced across experimental conditions, and had solid statistical results. In science, we call this good internal validity - since the experiment was well designed and implemented, we know the results are trustworthy.

I also buy the argument that knowledge about a story can help people enjoy it more. As the researchers mention, this speaks to perceptual fluency - the easier it is to understand something, the more we enjoy it. Whenever I see a book to movie adaptation, I always enjoy the movie better if I've already read the book. Movie trailers also help me understand what a movie is about. The same is true of non-story experiences - I like museum exhibits better when I already know about the artists and their artwork.

Emotional Investment

Star Trek Into Darkness has been occupying my mind for a very long time.

But the results of this experiment just don't apply to how spoilers are experienced in real life. This is called poor external validity.

People who complain about getting spoilers are really invested in the story they're anticipating. I've been looking forward to Star Trek Into Darkness since the movie was announced in 2009. THAT'S 3 YEARS OF ANTICIPATION! No offense to John Updike and friends, but I doubt any of the participants in this study were anticipating the short stories they were asked to read. While I don't have any data to back this up, my experience tells me that the more someone cares about a story and is looking forward to it, the more spoilers will affect them.

One of the reasons people are so affected by spoilers is because of the way things get spoiled. No one reads a spoiler right before they experience a story (as they did in this experiment). Real life spoilers happen in an elevator on the way to work when random strangers vent about who got killed in last night's Game of Thrones. People hate spoilers because they happen out of our control in situations we never anticipate about stories we love. Spoilers aren’t sought-out, they’re an unwanted experience that happens to you. None of that is reflected in this experiment (poor external validity).

Enjoyment versus Anger

What I want to do when I hear spoilers.

This experiment measured how much individuals enjoyed literature that was spoiled for them. But if you talk to anyone who's experienced a spoiler, they usually talk about getting mad. Anger at having a story spoiled and enjoying a story are two very different things. I'm still going to love watching Star Trek Into Darkness next week and I'm really upset that I don't get to experience a JJ Abrams mystery box. It’s a dialectic - both emotions can occur at the same time (though I'll probably adapt to my anger well before I see the movie next week). Unfortunately, this experiment didn't measure anger.

Experiential Avoidance

Films like North By Northwest are difficult for people who struggle with strong emotions.

Some people don't care about spoilers. Part of that comes from a lack of emotional investment in a story. Most of my non-Trekkie friends wouldn't care about the Star Trek Into Darkness spoiler I know - the movie is just another summer blockbuster to them.

But another huge factor is how you approach strong emotions. For a lot of people, intense suspense isn't a fun experience - it's something to be avoided. Psychologists call this experiential avoidance - the tendency to avoid thoughts, feelings, memories, and physical sensations that are unpleasant. For people who hate suspense, intentionally reading spoilers could really improve their movie watching experience. Think about watching any Hitchcock film - if you're very sensitive to suspense, knowing what's going to happen beforehand could be the difference between enjoying the movie and being tormented by it.

Experiential avoidance was not evaluated in this study.

Future Research

Despite everything I just wrote, I really do like this experiment and emailed the researchers back in November to praise their efforts. However, like any new line of research, there are a lot of ways in which the study can be improved.

The idea that emotional investment impacts the experience of spoilers needs to be tested. You can easily do this in an experiment by artificially inflating the expectations of one group of participants (e.g. have someone in the waiting room tell the participant how cool the story they're about to read is). You could also increase external validity by having stories spoiled in more realistic ways (e.g. the experimenter reveals the ending of a story completely out of context). Researchers can also easily integrate measures of anger about spoilers and assess experiential avoidance related to suspense.

People experience stories for a wide variety of reasons. I love Star Trek, but I don't care if someone tells me the ending to The Hangover Part III. Making blanket statements about how spoilers are experienced without integrating the complexity of real life just isn’t good science.

May 12, 2013 Update: Someone just sent me Jennifer Richler's article about spoilers from The Atlantic. I didn't read her article before writing this one, but I'm happy to see we share many of the same ideas about why spoilers are so bad.