The Walking Dead's Scott M. Gimple has done a fantastic job with the fourth season. The show continues to raise the stakes and weave in and out of the comic's continuity in interesting ways. I was especially interested in what was happening to the kids living in the prison and started writing an articled called How to raise a child in the zombie apocalypse. After this week's episode, I completely abandoned that article and dove into the psychology behind what's become the most controversial event in the show's history. Spoilers ahead for The Walking Dead Season 4 Episode 14 – "The Grove".

Read MoreCOSMOS tells a great story, but it forgets to explain the science of denying science

COSMOS: A Spacetime Odyssey is presented by FOX Sundays 9/8c and National Geographic Mondays 10/9c

I've been anticipating COSMOS: A Spacetime Odyssey ever since it was teased at last year's San Diego Comic Con. Carl Sagan's original Cosmos: A Personal Voyage was a big part of my childhood and, along with Star Trek, it made me believe that science would create a better future for humanity. Knowing that COSMOS was returning in one of the biggest television rollouts of all time with the coolest modern scientific communicator (Neil deGrasse Tyson) made me a very happy nerd.

Neil deGrasse Tyson's got the right stuff to take on COSMOS.

The first episode explains Earth's position in the universe and introduces the cosmic calendar to a whole new generation of people. Both had the effect of making me feel impossibly small & completely inspired. What was unexpected was the story of Giordano Bruno, a man who argued that the Earth orbits the Sun in an era when most believed the Earth was the center of the universe. Bruno died for his beliefs and in telling this story COSMOS makes a clear case for the scientific method of questioning everything. The episode tells a great story, but it forgets to explain the science of why people deny science.

Stories are persuasive

A history of the universe, condensed into an easy to understand story.

What made COSMOS so effective is Tyson's mastery of storytelling. He's been doing this for years at the Hayden Planetarium, on Capitol Hill, and across television networks (probably because he was inspired to follow Sagan’s example). Tyson easily translates complex ideas into straightforward language that gets people excited about understanding space. Most scientists can't do this and have a hard time sharing their ideas with people who aren’t in their field. Check out Tyson at his best in the "We Stopped Dreaming" speech.

Stories aren't just entertaining. They’re an essential part of our psychology. The brain creates a story of who we are based upon the experiences we’ve had. These stories are simplified versions of reality (cognitive biases filter much of what happens to us). We're also biased to remember supernatural things like singing frogs (remembering things that are unusual helps us stay alive). But regardless of accuracy, stories are important because they have a huge impact on how we think, act, and feel.

The key stories from the first episode of COSMOS include:

- The Earth is a tiny part of a vast universe.

- Humanity didn't always believe this and people like Giordano Bruno were killed for asking too many questions.

- Humanity has existed for a very small amount of time compared to the rest of the universe.

Each of these stories is backed by science, with the exception of Bruno's story. COSMOS fails to explain why people rejected Bruno’s ideas and why many continue to deny modern day scientific truths (like climate change).

We attack information that conflicts with our stories

Cognitive dissonance explains why Giordano Bruno was attacked for his views of the universe.

The best explanation for why people deny science comes from Leon Festinger's study of "The Seekers". Festinger infiltrated a cult led by Marian Keech who claimed to be receiving messages from aliens telling her the world would end on December 21st, 1954. Keech also claimed that she, along with her followers, would be saved at midnight prior to the end of the world. Her devotees left their jobs and stayed with Keech for the week leading up to the 21st. Midnight came and went – nothing happened. Instead of coming up with a rational explanation for why they weren’t beamed up by aliens, the seekers believed that God was so impressed with their prayers that he saved the world.

Festinger tested this experience in the lab and developed cognitive dissonance theory. Basically, we try to be true to the stories we tell ourselves. When there's a clash between our beliefs and new information (The Earth is the center of the universe but this guy is saying the Earth moves around the Sun), we unconsciously find information that fits our personal stories and end the conflict (He’s a crazy heretic). Cognitive dissonance is another part of the psychological immune system that keeps us feeling good about ourselves and the choices we make. Chris Mooney summarizes it nicely:

…our positive or negative feelings about people, things, and ideas arise much more rapidly than our conscious thoughts...That shouldn't be surprising: Evolution required us to react very quickly to stimuli in our environment…We push threatening information away; we pull friendly information close. We apply fight-or-flight reflexes not only to predators, but to data itself.

The brain attacks information that might challenge our beliefs the same way antibodies fight viruses. We unconsciously morph new information to fit in with existing stories (Sure, smoking isn’t healthy, but I don’t smoke that often and when I do they’re lights). Research has also shown that the harder you try to change someone’s perspective on an emotional topic, the stronger their existing point of view becomes. That's why debates on abortion don’t go anywhere and just make people mad.

How do we get around the problem of cognitive dissonance? New information has to be communicated in a way that fits in with someone’s existing stories. That's one of the reasons why many Jews, Christians, and Muslims believe in the big bang – it’s consistent with many religious stories about genesis and creation. It’s also why some people of faith have a hard time with evolution – the cosmic calendar doesn’t align with many religious texts.

COSMOS doesn't look like any documentary we've seen before.

COSMOS, a big budget primetime miniseries that looks more like a science fiction blockbuster than a science documentary, is perfectly positioned to get around the barriers of cognitive dissonance because it tells a cool story. I’m bummed it didn’t explain why people rejected Bruno’s convictions, but I believe it will inspire a new generation to love science.

Rating: 9/10

To learn more about the science of science communication, check out Kyle Hill’s article at Discover Magazine.

The Psychology of Star Trek VS. Star Wars: Episode III Live at WonderCon 2014

Join me and Dr. Andrea Letamendi (Under the Mask Online) as we bring our popular intergalactic sci-fi battle back to WonderCon for round 3! We'll step into the pop culture ring to debate the science behind the families, friendships, and relationships of science fiction's two legendary franchises. Special guest panelists include actors Chase Masterson (Star Trek: Deep Space Nine) and Catherine Taber (Star Wars: The Clone Wars). Join a side and cast your vote as we crown one the winner! Refereed by Brian Ward (The Arkham Sessions).

Saturday April 19, 2014 7:30pm - 8:30pm Room 213

Nerd Nite at 92Y's 7 Days of Genius

I had the honor of giving an encore presentation of my Nerd Nite talk on the psychology of Star Trek's utopian future at 92 Y's 7 Days of Genius this week. Full video of the event is available below! Matt Wasowski starts with an introduction of Nerd Nite, David Shuff talks Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ride at the 8 minute mark, Neil Janowitz shares the secret history of Tetris at 35:50, and I discuss 3 easy steps to create Star Trek's utopian future at 1:02:40. Enjoy!

Georges Méliès's A Trip to the Moon Reveals the Psychology of Film

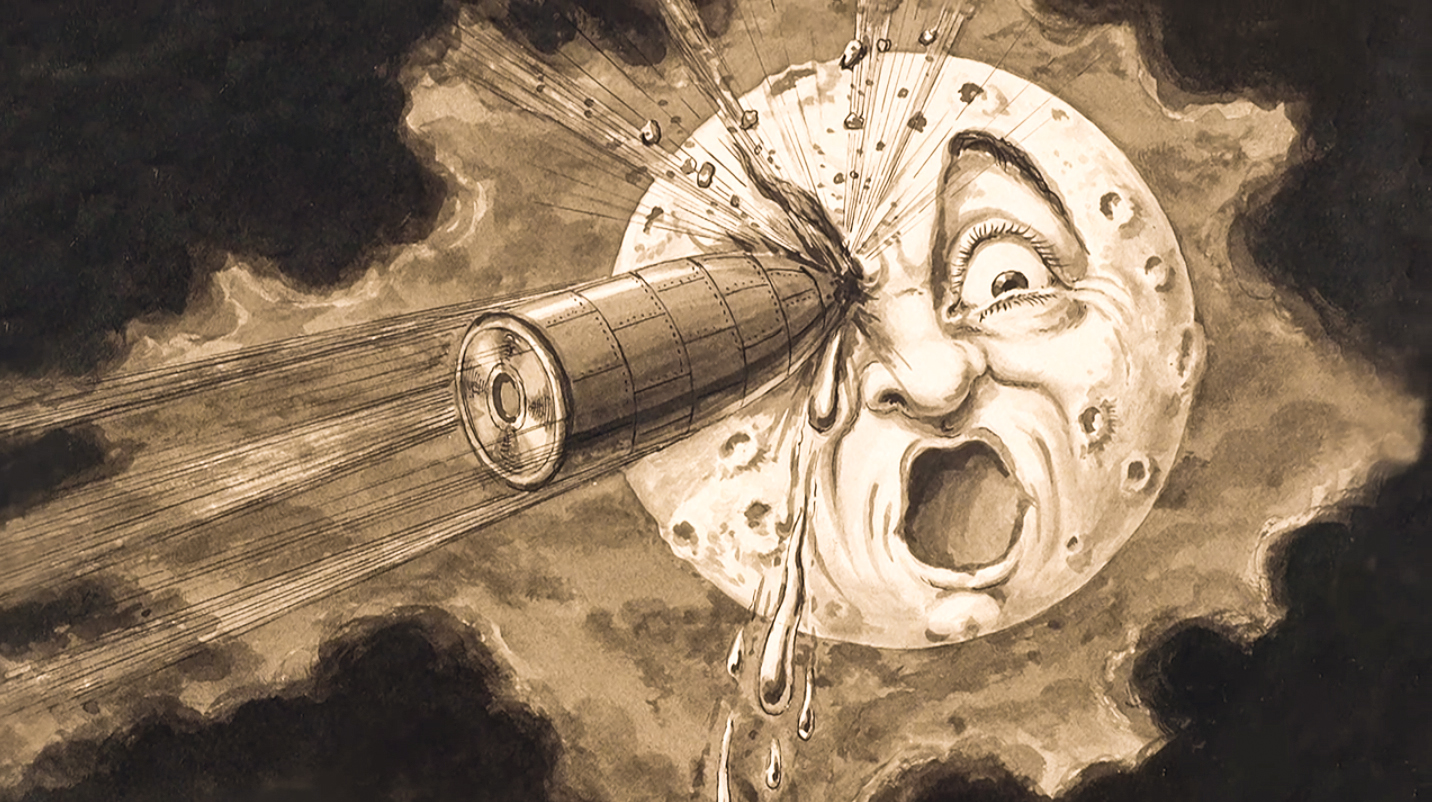

Original artwork from Georges Méliès's A Trip to the Moon.

Recently, I wrote about how 2013 was the most honest year of my life. 2014 is about taking the next steps into the world of geekery. That's why I launched the Super Fantastic Nerd Hour podcast with H.A. Conrad and why I'm starting a new project here at Brain Knows Better.

Starting today, I'm going to explore the psychology behind the greatest science fiction films of the 20th Century. I'll keep writing about new movies as they come out, but I thought it would be fun to revisit the foundational stories that make this genre so awesome.

I'm going to move chronologically and start with the first science fiction film ever made – Georges Méliès's 1902 Le Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon), a film that unravels how cinema works and highlights the elements of all successful science fiction movies.

The Psychology of Film

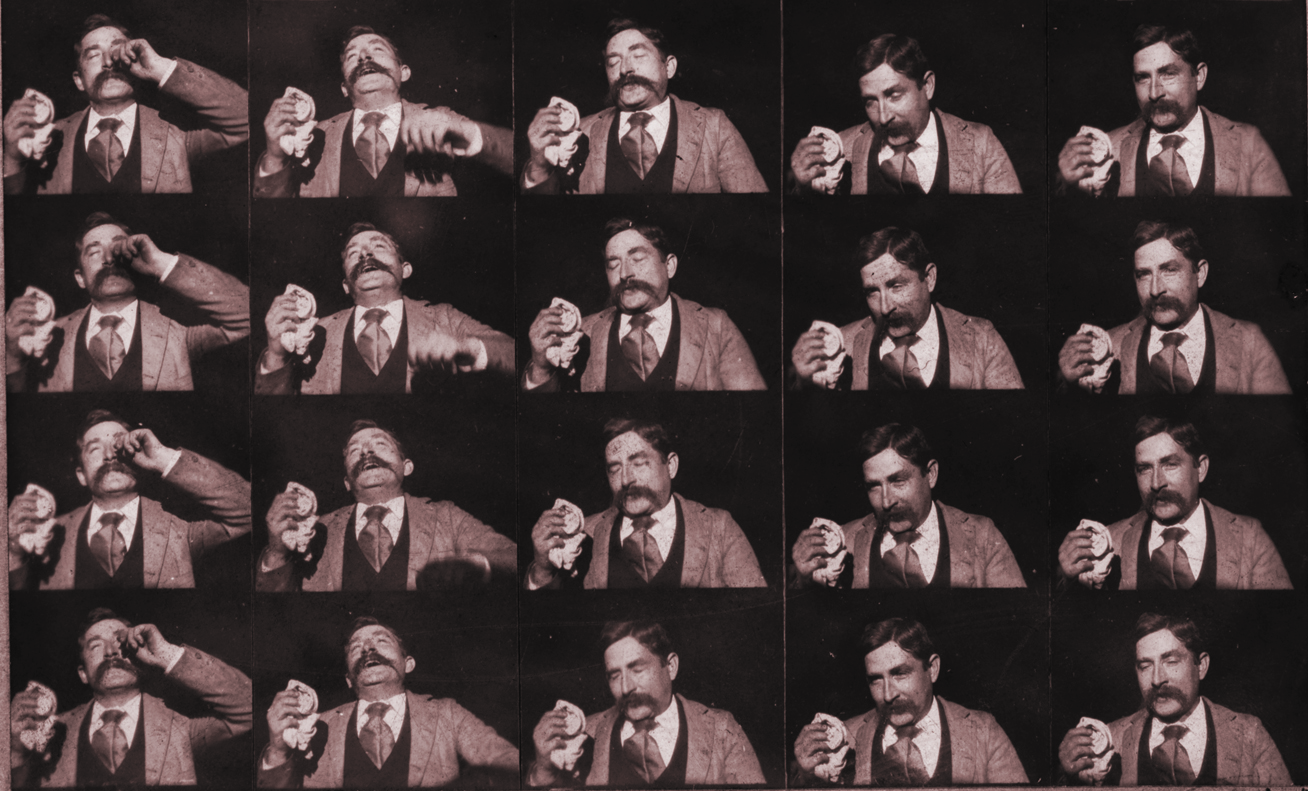

Early films recorded moments of daily life, like this Edison film of a man sneezing.

At the beginning of the 20th century, cinema was still in its infancy. Most films were brief, non-edited scenes of daily life – crowds in a city, vaudeville performances, or if you were lucky, glimpses of a far off land or new technologies like the locomotive.

Méliès started filming the same way by documenting life in Paris. But thanks to an accidentally jammed camera, he learned that if different scenes were stitched together your eyes fill in the blanks and experience the film as one continuous story. Méliès combined this discovery with his knowledge of magical illusions and created the first generation of cinematic special effects.

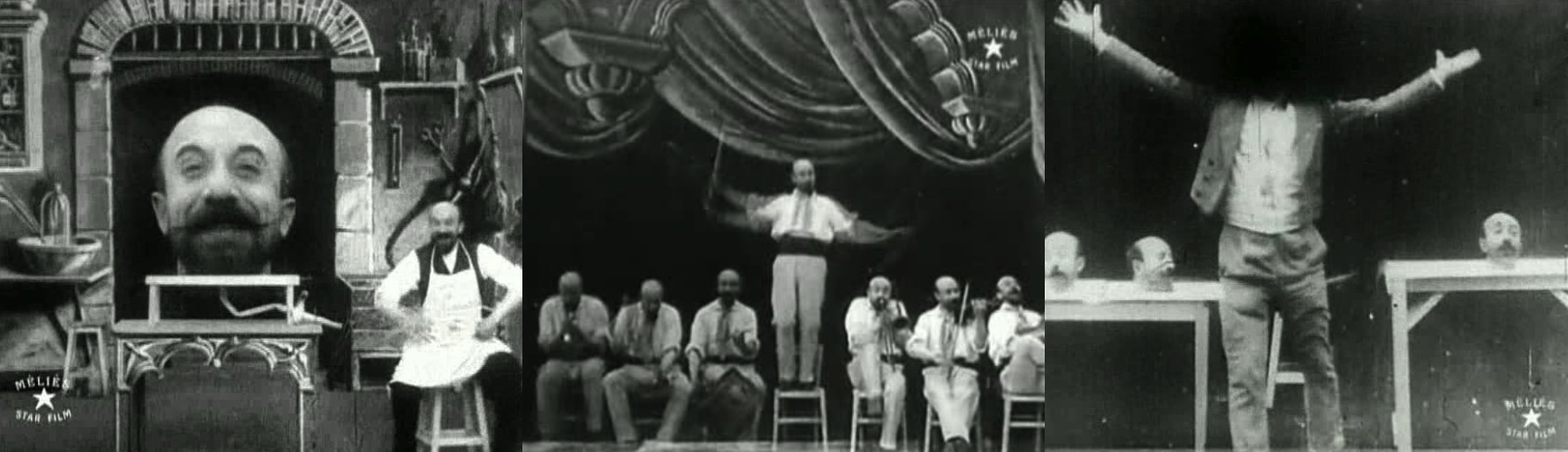

Méliès's pioneered the use of film special effects.

Méliès's "trick films" worked because our visual system has built in shortcuts for motion detection called visual persistence and the phi phenomenon. Why do these shortcuts exist? All of our senses are wired to detect change and ignore things that stay the same. Being able to quickly see movement really comes in handy when you're avoiding dangerous animals or hunting for food.

Tricking your eyes into seeing motion isn't enough to create a good film though. Méliès pioneered film editing for the purpose of telling visual stories rather than just documenting reality. He wasn't the first to do so (see Alfred Clark's The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots), but his films popularized cinema in a way no other filmmaker had ever achieved up to this point in history because Méliès created stories that could only be told in film.

Thanks to neuroscience we now know that edited films like Méliès's lead to similar changes in brain activity across audiences. Edited films increase activity in areas of the brain responsible for vision, sound, language, emotion, facial recognition, and conscious thought. Even eye movements match up when a group of people watch an edited film. Unedited scenes of daily life don't have this effect – everyone’s brain reacts differently. So the more tightly you edit your film, the greater influence you will have on someone's brain. That's probably why film edits have become quicker and faster throughout the 20th century.

A tightly edited narrative combined with stunning visual effects helped A Trip to the Moon become first international motion picture hit.

Creating a Popular Science Fiction Film

The launch cannon from A Trip to the Moon.

The plot behind A Trip to the Moon is pretty simple – a group of professors uses a giant cannon to launch themselves to the moon and then take a nap on the lunar surface, kill a bunch of moon aliens, return to Earth with a splashdown in the ocean, and celebrate their journey with a parade in the city.

The story might sound simple now, but audiences back then loved it. We don't know much about the film's early reception (there's a story about how its first audience applauded for hours after seeing the film) but we do know the film was in high demand. So much so that negatives were stolen and pirated across the world. Nearly all of the copies shown in America were illegally duplicated by Thomas Edison and removed any mention of Méliès. Rival studios made similar films about trips to the Sun and Jupiter. Then there's “An Excursion to the Moon” which is a complete plagiarism of Méliès's work. Sadly, Méliès never saw any of the profits from the illegal duplicates of his film.

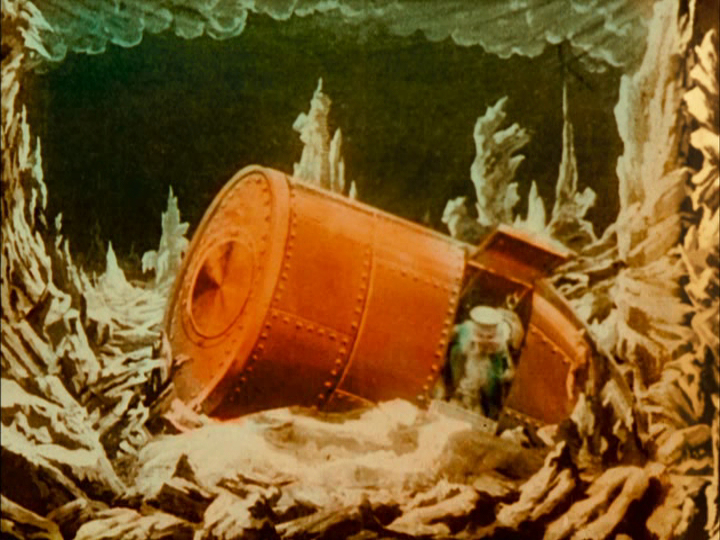

Landing on the moon.

What made A Trip to the Moon such a popular film? An innovative psychological study offers a few clues. Stephan Schwan and Sermin Ildirar were interested in understanding what happens when someone watches a video for the first time. They found a group of adults in remote regions of Turkey who had never seen a video before. The researchers studied their responses to watching edited films and compared the results with people who were more familiar with video. People who watched film for the first time understood the basics of what is happening onscreen but were confused by some of the editing and misunderstood details of the story. However, people who were familiar with the ideas of a video (cooking a meal, preparing tea, or transporting wood) could understand the story and weren't confused by the edits. People who had more prior exposure to video understood everything, even if they weren't familiar with the ideas in the video.

To sum it up, the only way to fully understand a visual story is by either watching a lot of television and movies or being very familiar with the ideas in the story. For A Trip to the Moon, most of the audience didn't have much experience watching films, but they were VERY familiar with the ideas in this film. Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon, released 37 years before this film, had popularized the idea of space travel. H. G. Wells's The First Men in the Moon expanded on Verne's work by introducing a race of insect-like moon aliens called "Selenites". The tone of Méliès's film mirrors that of Jacques Offenbach's A Trip to the Moon operatic parody of Verne's novels while the structure of the film follows that of an attraction at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in New York.

The Selenites.

A Trip to the Moon was a success because it summarized ideas already popular in culture and presented them in a stunning new way. That's why films like Planet Of The Apes, Star Wars, Back To The Future, and The Matrix were so popular while 2001: A Space Odyssey and Donnie Darko were appreciated by people who had watched a lot of science fiction.

People like watching movies where the hero wins, appreciate films that make us think, and feel enriched by stories that make us ask big questions. What makes the science fiction film genre so amazing is that it’s capable of achieving all of these goals in one story. A Trip to the Moon wasn't just an enjoyable experience; it made audiences reflect on the possibilities of spaceflight and dream of what would happen if we met an alien life form. You can connect the dots between this film and the Apollo 11 moon landing.

Celebrating a successful return to Earth.

As films evolved, Méliès couldn't adapt to new cinematography techniques and quit the medium. Martin Scorsese does a great job telling the story of what happened next in Hugo. Most of us now get exposed to Méliès's work through pop culture references (like the beautiful homage in The Smashing Pumpkins Tonight, Tonight music video) or in film classes. But the core elements of all modern science fiction films, exploration of the unknown, futuristic technologies, new life forms, social commentary, and state of the art special effects were all brought to life for the first time in A Trip to the Moon. It is the foundational work of art that made all future science fiction films possible.

View the film in its entirely below.